Goodbye East Berlin

November 9, 1989. The images I never thought I’d see: People, lots of them, by and on top of the infamous Berlin Wall. Whole sections of it coming down. It was a miracle unfolding before our eyes.

On a train to Berlin — July, 1990

I rode the train from Cologne to Berlin overnight as I had several times before. Except this time, the border controls were gone and the train stopped in Magdeburg (in former East Germany). A guy carrying a unicycle came into the compartment I was in. It was very early morning and I just made a mental note of the unusual carry-on. Then back to sleep.

Later I woke up and looked out the window when the train stopped in Potsdam, just outside Berlin. Minutes later the train was already speeding along through the forest and suburbs inside Berlin.

I thought back to prior times taking the train from Cologne to Berlin.

On a train to Berlin — August, 1975

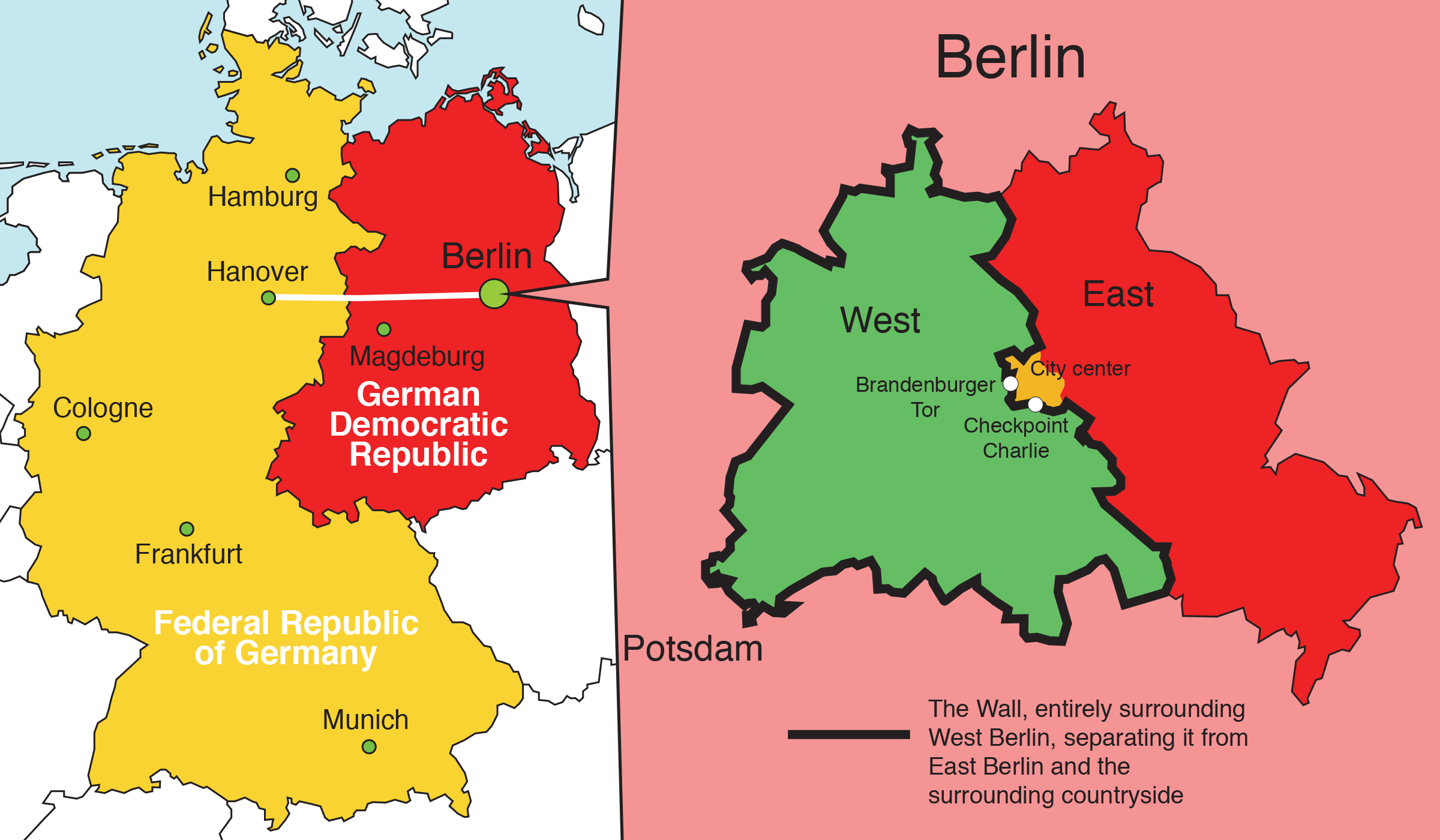

Normal stops in West Germany. Then a long stop at the border at Helmstedt. Lots of fences, floodlights, armed guards, checking under the train cars to make sure no one was hiding there (like anyone would really want to escape INTO East Germany). As the train rolled on, through East Germany to perform its duty as a transit train (just passing through, thank you very much), a uniformed border police officer with a portable desk hanging on his stomach, would make the rounds. He checked everyone’s passports, added requisite stamps and inserted a paper slip, the all-important transit visa.

I always wondered what would happen if at the end of the trip (on a train that didn’t make any scheduled stops in East Germany), one didn’t have that transit visa. Probably best not to find out.

As the train eventually neared the border to Berlin (there to repeat the process of inspection), the border police with his portable desk came by again. Checked passports again. Collected the little transit visa slips. German efficiency at work. I always wondered if those men truly believed they were doing a very important duty to protect the Fatherland.

It was a transit train. Legally just passing through. I was in East Germany, but not really in East Germany. They could have locked the doors at the first border crossing and unlocked them at the exit one. But that was probably too simple. Plus this way, they had a record of everyone who took the train from West Berlin to West Germany.

If one had any concerns about being found and dragged off the train, all one needed to do was fly out of Berlin to any point in West Germany. No transit visas or East German passport checks on the airplanes. Yes, it was a silly charade, all that checking on the trains. A way to harass people and let them know who was boss.

Back to July, 1990

This morning, none of that had happened. Because I made my trip after the reunification of Germany. Everything had changed.

I realized just how much a few hours later. In the plaza by the ruin of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, I saw the guy from the train. Doing tricks on his unicycle. Apparently donations from passersbys made the trip from Magdeburg worth it for a street performer. Free enterprise at work.

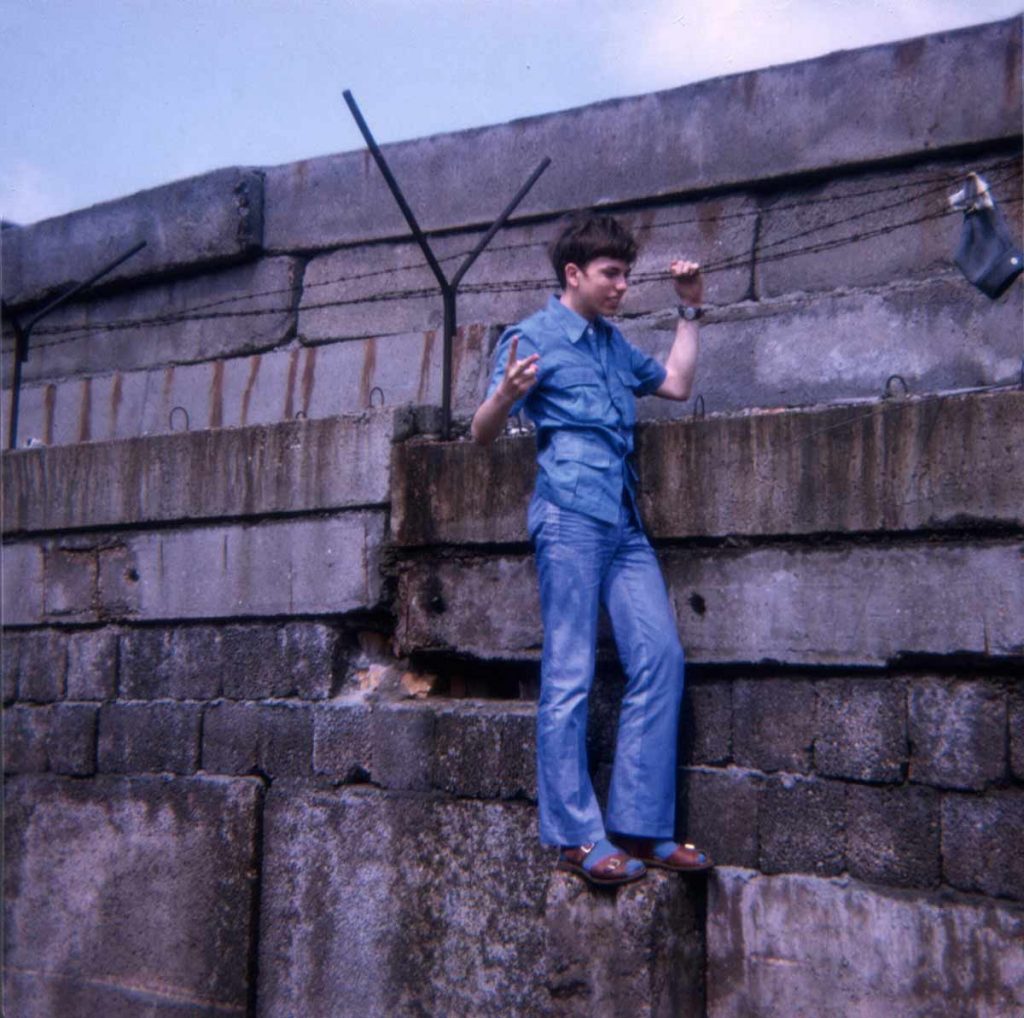

First sight of the Wall, May 1971

In 1971, when I visited West Berlin for the first time, I remember standing in front of the Wall, a cobbled together mess of odd construction blocks, topped with rusting barbed wire. My overarching thought was that I would not see it come down in my lifetime. The Wall had already been there for 10 years. I fully expected it to be around for many decades more. Because the communist regime was so entrenched and surely the Soviets would never give an inch here.

My host family, the Haumersens, excitedly told me about how the Christmas before they’d been allowed, for the first time since the Wall went up, to for a few hours go over and visit relatives that lived a few miles away, as the crow flies. But thanks to the Wall, in another world.

All that changed almost overnight on November 9, 1989. It was actually a process that took months, but the final straw came overnight. Suddenly the world was treated to video images of people climbing on top of the Wall in Berlin. Waving flags and hugging. The formerly sealed border was thrown open. Life changed.

Another year and East Germany was history. Germany reunified. Berlin was again one city.

July 1, 1990 – Currency reform

The day in July 1990 that I was there was when the currency union took effect. After World War II, West Germany created a new currency: Deutsche Mark. While East Germany created theirs: Eastern Mark. Officially the 2 currencies exchanged 1 for 1. Holding them in your hand, you could feel a difference. DM coins felt like other countries’ coins: Hefty. Like they were worth something. Eastern Mark coins weighed next to nothing, being all aluminum. Didn’t feel like money or value.

Going into East Berlin as a day tourist, you were required to exchange a prescribed amount into East Marks. Then on leaving, you were forbidden to take any East German currency out with you. Use it or lose it.

Being a teen wanting souvenirs on my first trip to East Berlin in 1971, I squirreled away coins and bills in my socks and under the bottom of my shoulder bag, before going through the exit check. Obviously rather stupid. Because there’s no explaining that away if strip-searched. But teens think they’re invincible. Still have those souvenirs.

And here I was again in Berlin, freely riding trains across the former border. Able to use regular Deutsche Marks everywhere, East or West. No more aluminum coins.

I was one of the many people at Checkpoint Charlie chipping away at the remaining concrete sections of the Wall to get a few souvenirs. Enterprising vendors rented out tools for chipping. Or you could just buy a piece of the Wall from one of the display tables.

It was like going to a big party.

Bus ride in East Berlin, 1974

I was in East Berlin to see my pen pal. Read more about that here. Like other times, I crossed the border at Checkpoint Charlie. Then found a bus that would take me to where she lived. Back in West Berlin, I was used to paying the driver when getting on a bus. Or maybe a roving conductor.

Not so here. Instead there was a fare machine near the middle doors of the bus. Decidedly low tech: A wheel with compartments behind a glass front. When I dropped my fare in, it landed in one of the compartments. So everyone could see what I’d paid.

But since the device didn’t actually count what I dropped in, to my western mind, this was like inviting cheating. I could drop anything in there and get a ticket. Not that those aluminum coins felt worth anything much anyway.

Of course it wasn’t that easy. Because everyone on the bus would see what I dropped in. And that fear of what someone else would say kept people in line. Officially this system was known as Gesellschaftliche Fahrkartenkontrolle (we might call it crowdsourced ticket control). Here is a picture and text about the fare box (in German).

East Germany survived in no small part due to this system of encouraging people to spy on each other and informing the authorities of anti-proletarian activities or attitudes. Because you didn’t want to find yourself in a reeducation camp or sent off to a remote corner of the country as punishment for saying or thinking something that wasn’t in line with the official party narrative. Fake news at its best.

Berliner Funkturm am Alex, 1974

The incongruity of the Berlin Wall surrounding the entirety of West Berlin, sealing it off from East Berlin and East Germany was nowhere clearer than if you went up to the observation deck in the tall Fernsehturm (TV tower) at Alexanderplatz in East Berlin’s traditional city center. It was and is the tallest structure in Germany.

When I was over visiting my pen pal, her daughters took me up in the tower, proud to show off this then rather new marvel. As we stood up on the observation deck, 665 feet above the bustling city, if I looked to the west, I clearly saw the Brandenburg Gate less than 1.5 miles down the street. That was where the Wall was. Beyond that, I saw the entire West Berlin spread out.

I wanted to ask the girls how it felt to be able to see what was over there and not go there. Of course I didn’t. Because I didn’t want to risk embarrassing the girls. And I had no idea who else might be listening to the conversation.

What I got from the girls was excitement about the view and the technological marvel accomplished by their country. I agreed that the tower was marvelous indeed.

Back down on the ground, it was time for me to head back to the West. I gave the girls all my East German money. Because I wouldn’t be allowed to take it out with me or change it back to “real money”.

A restaurant in East Berlin, August 1975

I wasn’t actually there for this event. I learned about it later, from 2 of the people who were there. Independently.

I met Adis and Debbie in Berlin 1975. A day or two later, they were with other Americans visiting East Berlin for the day. At lunch-time, they found a local restaurant. Since the group was larger than would fit around one table, someone proceeded to pull 2 tables together.

A waiter quickly made them put the tables back the way they were originally. I’m sure no one in the group was even aware that they had broken rules about public gatherings by pulling tables together. The restaurant and the waiter could have been in trouble.

The meal proceeded and at some point Adis decided to take a picture of the group. Perfectly normal thing. Because you want a memory of the day.

Next thing she knew, there was a Russian soldier right in front of her. Demanding she hand over her camera to him. Because you’re not allowed to take pictures of anything military. And he and a buddy or two were at a nearby table. In uniform.

Adis managed to rescue her camera, but had to give up the roll of film. With who knows what other pictures of the day and probably previous days as well.

After that adventure, the group left the restaurant. Or was maybe asked to leave. Not sure which.

All in all, the young people in the group were fortunate. It could just as easily have ended up with police showing up and everyone hauled off for questioning, before eventually being released and sent across the border, with an admonition never to return.

No wonder people in East Berlin were careful with what they did or said anywhere. Somebody was always watching. Ready to report suspicious activity. Or just make a report to cause trouble.

A Wall for protection

The Berlin Wall was officially built to halt capitalist aggression against East Germany. In reality, it went up to stop the bleeding. Autocratic, dictatorial East Germany was dying.

So many people were leaving for West Berlin daily that society couldn’t function. They had to put up the Wall or die. But the Wall divided a people with a common history. The Wall was the answer to a manufactured crisis. The leaders of East Germany wanted to stay in power by all means. Including putting up a wall to keep their own people from leaving.

In the end, East Germany died anyway. It just took longer. 28 years longer.

And then, rebirth

With historical downtown Berlin all in East Berlin, West Berlin developed a new city center and areas close to the Wall became the home of Bohemians, artists and squatters in neglected tenement houses. Nobody seemed to care. Until the Wall came down. All of a sudden those backwater areas were back to being prime real estate.

It wasn’t long after reunification that German government moved back to Berlin. Now the city was of interest for multinationals wanting to relocate there. It was back to being the crossroads of East and West of old. Today, if it weren’t for a paved line in the streets, you wouldn’t be able to recognize where the Wall once was or what was East Berlin and what was West Berlin.

I sensed exuberance and relief on my visit in July 1990. Berliners wanted to get on with life. To find the new normal and move forward. But adjusting to that change wasn’t all easy.

Finding a way forward

For some it was about embracing new opportunity as the city moved from being a backwater to new prominence. For others, the new, faster pace and development that changed everything they were used to was overwhelming and bewildering. In response, we got Ostalgie. A nostalgia for the good old days in the old East. Maybe not so good, but at least we had jobs and knew what the world was like.

Change is never easy. We transition from something we knew, but that is irrevocably gone, to something we don’t know (and feel we can’t control), but is coming at us whether we want it or not.

Autocratic/authoritarian/repressive regimes all come with an expiration date. And presumably all subscribe to the old saying: Apres moi, le deluge. They don’t care for what happens to those under their control. Not while in power. And certainly not afterward.

I haven’t been back in Berlin for a long time now. But I’m confident that as the communists couldn’t destroy its soul (or the Nazis before them), neither will capitalism. Nor will being thrust back to be the capital of Germany. Berlin was in so many ways the city that refused to die. And still is.

The Wall on the other hand, is long gone. Except for a brick line in a street, it’s not apparent where it once went. And that is good and well. I can go up to Brandenburg Gate, which stood right on the line between East and West and step back and forth.

“I can go out, I can go in.”

Berlin the city is a testament that repression doesn’t ultimately work.

For more about Berlin, here are a few movies to help get an idea of life in East Berlin and the divided city:

The Lives of Others — Someone is watching over everything you do.

Goodbye Lenin! — Exploring the magnitude of change and confusion as the German Democratic Republic ceased to exist and was reunified with West Germany to be one country.

The Spy Who Came in From the Cold — John Le Carré’s classic Cold War novel turned into a gritty film prominently featuring the divided city. A world where no one can be trusted and everyone is expendable.

The Tunnel — The Wall was built to stop people from escaping to the West. Doesn’t mean they stopped trying. At least 140 people were killed at the Wall over the years.

Walled in: The inner German border — Video showing how the Wall worked.

Photo of Berlin city center at night by Stefan Widua on Unsplash

Other photos by Claes Jonasson, except as marked.

Never miss out!

Get an email update every time I publish new content.

Be the first to know!